The Role of African Americans in Building North Texas Railways

From Denison to Sherman

Interurban lines were early 20th century electric railways that primarily transferred passengers and mail from city to city before cars were widely owned. The first interurban railroad line in North Texas was built in 1901 to connect the railroad centers of Denison and Sherman. The two towns were served by a total of 10 steam railroads. The interurban line was an immediate success, due in no small part to the creation of Woodlake Park and Coursing Dog Racing Park between the two stops. The desire for recreation attracted heavy visitorship to the parks on weekends and helped spread word of the success of the new railroad line, generating weekend revenue.

Building a rail system from scratch is a complex operation, especially when capital for the venture is a matter of selling stock, getting franchise permission from the Texas State Legislature and obtaining rights of way from local cities, towns and landowners.

During the national period of interurban railroad building, at the beginning of the 20th century, many projects raised financing but the systems were never built, causing eager investors to lose their money.

From Sherman to Dallas

The apparent success of the Denison and Sherman interurban line led John F. Strickland, Osce Goodwin and M. B. Templeton to begin in 1905 promoting the concept of building a new electric interurban line from Sherman to connect with Dallas.

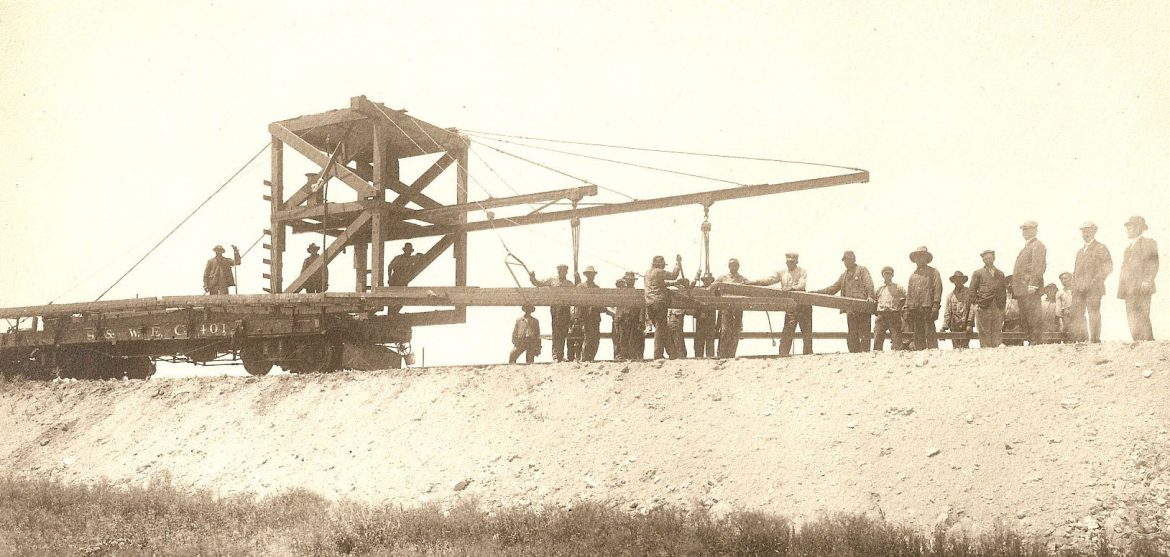

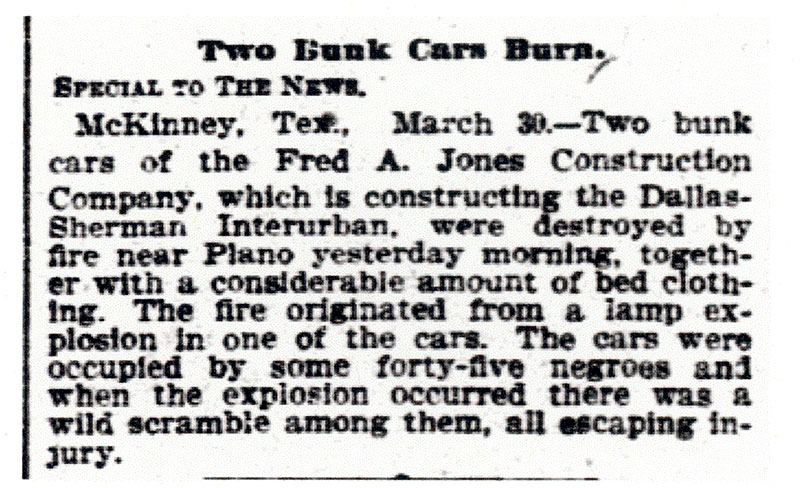

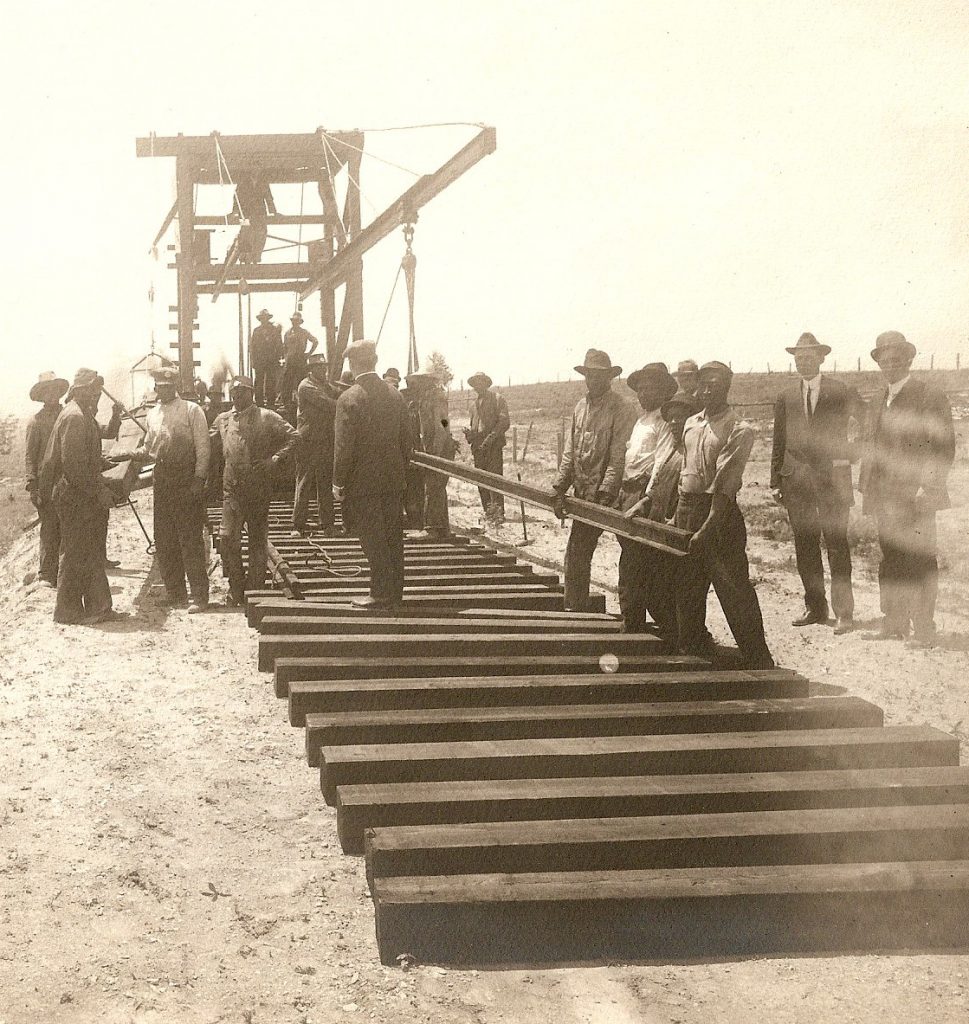

Design and construction of this new line was done by the Fred A. Jones Construction Company of Dallas. The Stone and Webster company of Boston was consulting engineer.

This line was constructed in 1908 and ran through Plano. The current Interurban Railway Museum at 901 E. 15th St. in downtown Plano was originally Plano’s interurban rail depot.

The Role of African Americans

Gandy dancers was a slang term at the time for railroad workers. And African Americans played a major role in building and sustaining the interurban railways in North Texas, including this new line through Plano.

From the earliest times in steam rail history in the American South, slaves bought and owned by southern railroads labored to do the arduous and unskilled labor to build railroads below the Mason-Dixon Line. In some cases, slaves even rose to semi-skilled positions. African American women, as slaves and after Emancipation, also worked on the railroads in a number of capacities.

The pool of rail building experience carried past the Reconstruction era into the 20th century where negro work gangs (as they were called at the time) were organized under a local or out of state labor foreman to extend the new “electric transportation magic” of the era into North Texas.

Throughout the South, African American men with railroad building and maintenance of way experience were recruited by independent labor recruiter/managers. These managers – sometimes African American and sometimes white – would negotiate with building contractors or rail project contractors for amounts of pay, hours and benefits.

If a project was out of state or city, the company would normally pay transportation in a box car to the work site and the men were housed in bunk cars. Bunk cars were rail cars used as sleeping quarters for laborers and would follow behind the progression of the track laying work, because the laborers were not permitted to leave the work site and were not welcome in small towns along the way.

Bunk cars were set up for eating and sleeping. In the evening after a day’s work, card playing and checkers were allowed. As railroad track was laid with the Windlass machine, the crew worked over the previously graded route. Grading and leveling was done by draft animals, mules and horses, which were in charge by African Americans.

Interurban bridges and trestles were built by separate companies that specialized in bridge and trestle construction. Such companies had their own African American crews that did the heaviest and most objectionable parts of the work.

Railroad Employment Was Prized Work

Although the work was hard and dangerous, African Americans, especially the men, were glad to get steady steam rail and electric interurban railway work. It allowed them to avoid the widespread convict leasing programs in the South, where men were forced to build railroads and county roads for no pay while serving out long, bogus jail sentences. It also allowed them to avoid the notoriously inequitable agricultural sharecropping system.

Working for railroad systems was steady work and lessened the chances for men to be caught “loitering” in a town square, waiting for a job in a “sundown town” – places where African Americans were not welcome after dark, of which there were many in Texas.

Through the early decades of the 20th century, African Americans slowly created a middle class for themselves, based in no small part on working for railroads and interurban rail systems. The job of sleeping car porter created by George Pullman made the black man’s face a permanent image seen on trains across the nation. Pullman Car porters stood at the top of the hierarchy of railroad work for African Americans. Both steam and electric rail owe a debt to the African American workers.

Learn more about the history of the interurban rail lines in North Texas with a visit to the Interurban Railway Museum in Downtown Plano.

Interurban Railway Museum > [codepeople-post-map]