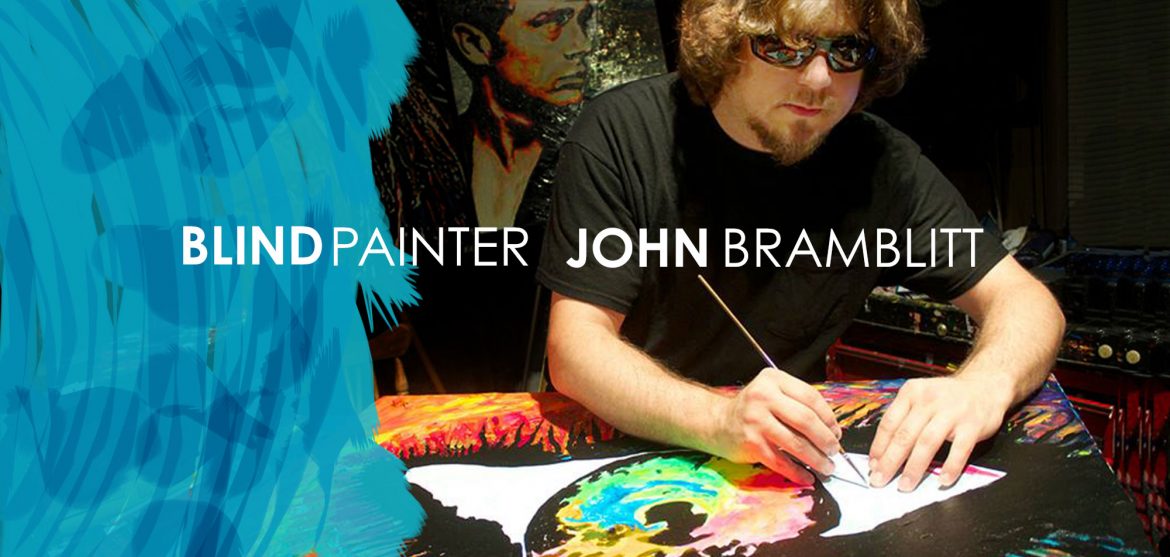

Before complications with epilepsy led to the loss of his eyesight, Denton artist John Bramblitt processed his world and his experiences through drawing. As he grieved and adjusted to a life with a secondary disability, John found that he felt isolated from people around him and even himself. John realized that he missed drawing, less because he couldn’t see and more because he wished to express himself.

And so it was that he began to dabble in painting by touch. At first, painting helped John to express the anger he felt about the changes in his life, but over time, he found that those feelings were replaced by a sense of peace and calm. Self-doubt gave way to self-confidence; aimlessness to purpose; and desolation to hope and joy. Through art, John rediscovered himself and found a way to connect with others, starting with friends and family and eventually branching out to the public.

John never anticipated, however, the extent to which his artwork would shape his life and touch the lives of others. “I didn’t even think of painting as therapy for me. I thought it might actually be a little dysfunctional, so I didn’t tell anybody at first,” he recounts. “But after six to eight months, I was so much calmer and happier. I wanted to do a show so I could meet other people who were just as obsessed as I was about art.”

Art shows led to news articles, which then led to connections with nonprofits and charities who approached John asking if he could whip up workshops for children with autism and seniors with Alzheimer’s. “The more I adapted art for different groups,” he says, “the more I would learn about art itself. And that really pushed me, because I was always learning new techniques and new ways to look at things, just through various forms of expression and accommodation. My art is way different now because of that, so providing therapy to others actually helped me in return.”

Nowadays, John Bramblitt works predominantly with museums in order to develop accessible arts programming. A visit to the Dallas Museum of Arts or the Southern Methodist University Meadows Museum, for example, might entail description and discussion of famous works, touching paintings or raised-line diagrams of them, listening to music from their respective periods of origin, and enjoying foods or perfume oils which may have inspired the artists’ creative processes. In addition, it’s common that attendees of John’s workshops, blind or sighted, may get their hands dirty and paint by touch as he does. These multisensory enhancements are beneficial to blind museum-goers, but what makes them universally accessible is that they enrich the experience for everyone involved, regardless of ability.

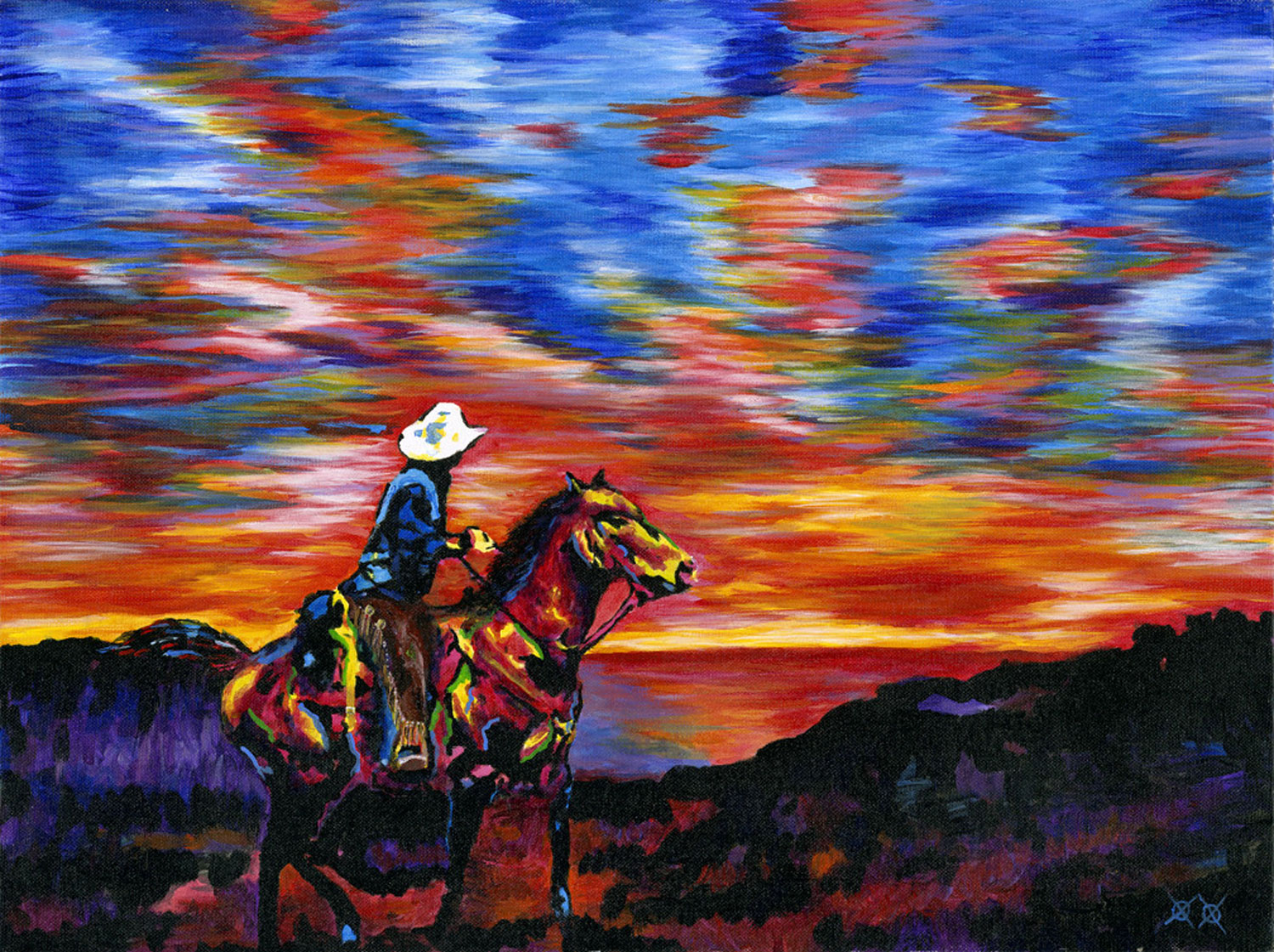

As an artist, John wishes not only to connect with others, but also to raise questions about matters of perception. “Vision loss really changed my way of seeing things,” he says. “Before I lost my eyesight, if I drew a picture of someone and it looked like them, I was happy. Looking back now, that seemed kind of shallow. Somehow, even though I’m blind, I feel like I’m more in tune with other people, because I’m relying on other modes of perception besides seeing. So when I paint someone now, it has to look like them, but it’s not right unless the colors match how they feel.”

John experiences synesthesia, which is an automatic association of sensations with one another. As such, his use of color is based on a combination of factors, including a subject’s physical features, personality, story, and overall vibe. His artwork is also strongly influenced by any music he listens to while painting. John rearranges the color palette and therefore challenges us to rearrange our expectations of what things should look like; and in this way, his artwork isn’t something merely seen—it calls upon us to be, to feel, to imagine.

“I think what keeps most people down tends to be themselves,” are John’s parting words of wisdom. “It’s like in painting. There are so many people saying ‘I can’t,’ but it’s interesting how, if you stop editing yourself—if you stop judging every little thing you do when it comes to art—you end up being able to do way more than you thought. It seems like it’s the same way in life.”

He continues, “When I lost my eyesight, I really thought everything was over because I already had epilepsy and all; but then thankfully, with the painting, I stopped thinking about it that way. I stopped editing everything I did, stopped worrying about the past or the future, and just focused on being in the moment. Things got a lot better after that. I wish more people would do that, because they don’t realize that what they’re capable of is incredible.”

John Bramblitt Art > John Bramblitt on Facebook >A version of this article was previously published on disability.gov.